Contents:

General information about strings:

In the orchestra the string section is split up into four segments; violins (I & II), violas, cellos and double basses. This is also the largest section in the modern orchestra with an average of up to 68 players.

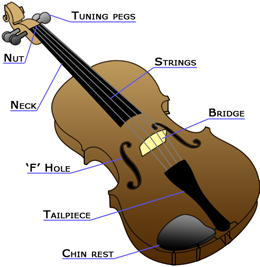

#1: Violin layout (click to enlarge)

Image #1 shows an example of how the instruments in the string family are laid out. This example is of the violin, but all the strings share a similar design.

Tuning

Violins, violas and cellos are all tuned in fifths, while double basses are tuned in fourths. The term ‘open string’ refers to the tone produced by the string when it is played with out being touched. Individual tunings for the strings can be found on their pages. Back to top

Fingering

For any string instrument to produce a note higher than its open string, the selected string must be firmly pressed onto the fingerboard at the desired position. This then shortens the strings length and produces a higher note when plucked or bowed. The left hand is used on the fingerboard to change notes when playing, to do this the player uses different hand positions.

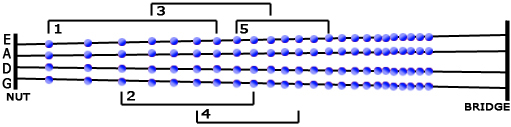

Image #2 shows an example of the first five hand positions that a violin player would use when playing. More details on hand positions will be found on their pages. Back to top

#2: Violin hand positions

Double-stops

It is possible to play more than one note on any string instrument, this is called double-stopping. This occurs when the bow is used usually across two strings to create a chord. It is possible to double stop with three or four note chords as long as each note of the chord is on a neighbouring string. These are called triple- and quadruple-stops.

When a triple-stop is to be played using the bow, more pressure is needed to produce sound from all three strings. The result of which creates a greater dynamic. It is not possible to sound all four strings at the same time using the bow. This is due to the curve of the bridge. For these to be successful, they must be played as an arpeggio. The same technique must be used on triple-stops if the dynamic needs to be quiet. The best triple- and quadruple-stops will use open strings, this is because open strings are able to sustain longer than fingered strings. Examples of individual double-stops can be found on their pages. Back to top

Bowing

Bowing is the act of bow in the right hand moving across the strings while the instrument is being played. This can be notated in music to aid the player in style and articulation.

Composers can use one of two symbols for an upward and a downward stroke of the bow. " " is used for a downward stroke and "

" is used for a downward stroke and " " is used for and upward stroke. These symbols are placed above the note they are intended to be used on. It is not necessary to place these symbols over ever note; the player will naturally choose how to play a piece of music without any symbols present. These symbols should be used to instruct a player how the composer wants the section to be played, to accent sections or even aid the player in difficult sections etc.

" is used for and upward stroke. These symbols are placed above the note they are intended to be used on. It is not necessary to place these symbols over ever note; the player will naturally choose how to play a piece of music without any symbols present. These symbols should be used to instruct a player how the composer wants the section to be played, to accent sections or even aid the player in difficult sections etc.

If slurs are not marked on the score (none legato) the string player will change bow direction on every note. The opposite is true for slurred notes. All notes under a slur will be played on a single bow, meaning one direction. This is legato playing. Back to top

Vibrato

This is used as an expressive effect on sustained notes. String players use vibrato (shortened to vib.) to improve the tone of a single note. This is done by pressing the finger on the finger board and moving it with a rocking motion while playing a sustained note. It is not always necessary to notate vibrato in a score, performers will usually add this naturally. If it was required for there to be no vibrato for a straight sound then this would be notated by using ‘non vibrato’ or ‘senza vibrato’ (‘senza’ meaning without). Back to top

Glissando

An effect where the performer slides from one note to another on the same string, either to a higher or lower note than the first. This is notated by a line between the notes to be played as a ‘gliss’. Sometimes the name is printed above this line, although it is not necessary. Back to top

Pizzicato

Another effect when performers ‘pluck’ the strings instead of bowing them. This produces a short sound. When performers are to play ‘pizz’ it is to be notated above the start of the section in the score and parts. When making the switch from pizzicato back to normal bowing, ‘arco’ must be written at the start of that section.

Snap (Bartók) Pizz

This is an adaptation of pizzicato; it is performed by plucking the string hard so it snaps back against the fingerboard. Notated by using " " above the note or writing ‘Bartók pizz’ above the stave if it is to be used in a longer section. Back to top

" above the note or writing ‘Bartók pizz’ above the stave if it is to be used in a longer section. Back to top

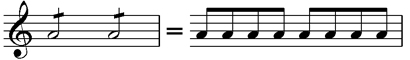

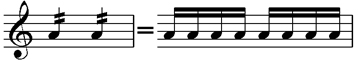

#3: Unmeasured tremolo notation

Tremolo

There are a few types of tremolo to remember:

1: Bowed and unmeasured

This sound is produced by short and rapid up and down strokes of the bow, constantly for the length of the note. It produces a rhythmic sound on the note, for example, it can be used as another method for sustaining long notes in a chord or to build tension. This is notated with three lines on the notes stem or over the note for a semi-brieve. E.g. image #3.

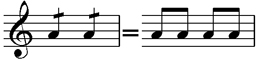

#4: Measured tremolo notation

2: Bowed and measured

This is shorthand used by composers if the same repeated rhythm occurs on a single note. For example (#4), instead of writing out a series of semiquavers that only us one note, the composer will write the equivalent length of the rhythm and place the lines on the note as in the unmeasured version above.

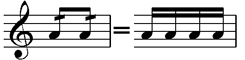

3: Fingered

This is, as the name suggests, a tremolo using the fingers. It is similar to a trill as it uses intervals of a second or anything larger. The performer, tremolos between two pitches using the fingers. The bow is used legato and slurs the notes together. #5 shows the notation of a fingered tremolo.

#5: Fingered tremolo notation

It is important to remember that when notating two notes for a fingered tremolo not to half the note values. For example, to write a fingered to fit the space of a crotchet, write both notes as a crotchet and not two quavers. This is the same throughout all note values.

#6: Rolling tremolo notation

4: Rolling

This is used when the two notes in the fingered tremolo are too far apart to be played on the same string. The notes are played on neighbouring strings and the bow rocks between the two as quickly as possible, slurred or detached.

#6 shows an example of the notation which uses the same principle as the fingered tremolo. Back to top

Sul Ponticello (On the bridge)

When the bow is used right up next to the bridge, the tone produced is tinny and creepy. This also produces upper harmonics that are usually not heard. To notate, write ‘Sul Ponticello’ (short; sul pont.) over the start of the section and ‘Natural’ (nat.) to switch back to normal playing. Back to top

Sul Tasto (On the fingerboard)

This is performed by using the bow over the fingerboard; it produces a soft, cloudy and obscure tone. To notate, write ‘Sul Tasto’ over the start of the section and ‘Natural’ (nat.) to switch back to normal playing. Back to top

Con Legno (With the wood)

To produce this effect, the bow is turned over and the strings are bowed using the wooden side. The sound produced is very quiet due to the lack of friction, compared to hair, but again creates a creepy tone. To notate, write ‘Con Legno’ over the start of the section and ‘Natural’ (nat.) to switch back to normal playing. Back to top

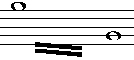

#7: Harmonics on D string

Harmonics

Natural

Harmonics are notes produce by very lightly touching the string at various and specific stages (these points are called ‘nodes’). These notes are overtones of the open string that they are played on (the fundamental). In fact, these overtones are can usually be heard when the open strings is played solo, the overtones are what give the fundamental is tone and colour.

By lightly touching any string of the violin at the half way point between the nut and the bridge, we stop the string from vibrating in its usual way. The vibrations are split into two halves on the string; this creates a note an octave higher than the fundamental with a clear, shimmering tone.

You can produce many harmonics on one string and these are called ‘partials’. The strongest of these are the first five and can be produced in the same way on all the strings in the orchestra.

The first partial is the fundamental or open string.

The second is produced by lightly touching the string at the half way point.

The third can be produced by lightly touching the string a third or two thirds of the way along the string.

The fourth can be produced by lightly touching the string a fourth or three fourths of the way along the string.

The fifth can be produced by lightly touching the string one, two, three or four fifths of the way along the string.

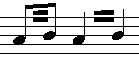

#8: Notation of natural harmonics

You can notate a natural harmonic in two different ways:

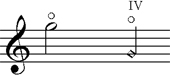

1: Place a small circle above the note intended to sound as the harmonic (image #8).

2: Place a diamond shaped note with the small circle above at the pitch where the node that produces the desired harmonic can be found on the string (image #8). Be warned though, some pitches can produce harmonics on more than one string. To get around this problem name the string above the pitch that the harmonic is to be played on. For example, just writing the strings name (e.g. G, D, A or E) above the pitch is sufficient. Some composers like to write the string names as a roman numeral. In this case they are named from highest to lowest, from I to IV (e.g. I=E, II=A, III=D, IV=G). This is true for all the string instruments.

Artificial

#9: Notation of artificial harmonics

These overtones sound the same as natural harmonics. The only thing that is different about the two is the way in which to produce them. These overtones are not tied to the harmonic series of an open string; you can produce a harmonic for any note with an artificial harmonic.

The performer plays a note as normal with one finger and with another from the same hand lightly touches the same string a forth above the stopped position, this produces a harmonic two octaves above the note being fingered.

To notate an artificial harmonic, write a normal note two octaves lower than the intended sounding pitch. Then place a diamond shaped note a forth above it, this tells the performer what note to play and where to place the node. Using a small circle above this will also make it clearer (#9). Back to top